Fifth Grade Essay on Why the Fine Arts Should Remain in Schools

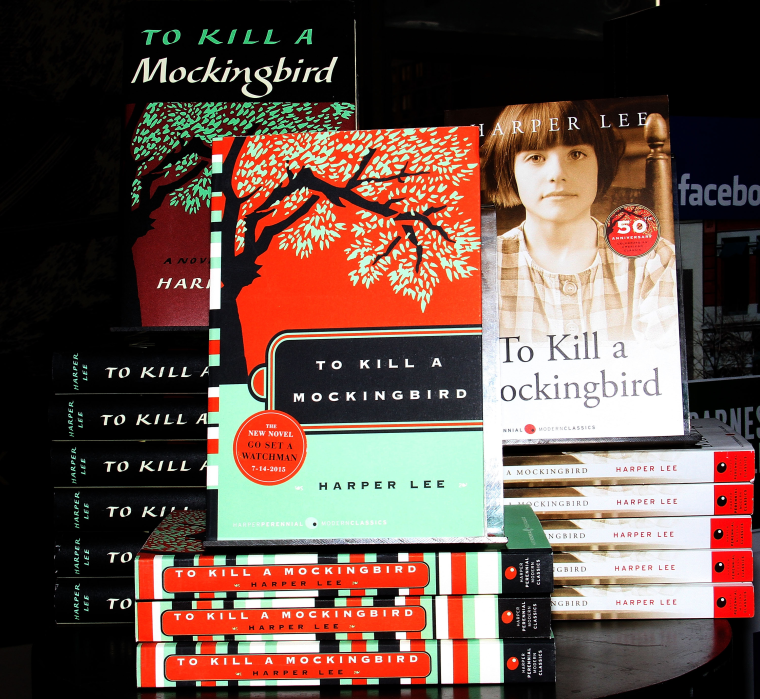

A Mississippi School Lath sparked outrage this month when information technology voted to cut "To Kill a Mockingbird" from eighth-grade reading lists in Biloxi. The issue? Some people complained that the book's language made them uncomfortable.

While the backfire was swift, those who blindly defend "Mockingbird" are missing an important bespeak. If the criteria for inclusion on a center school syllabus was simply whether the novel provokes tough discussions, Harper Lee'due south opus belongs in as many classrooms as possible. Merely that is non the just question.

Let's be clear: "To Kill a Mockingbird" is not a children's volume. It is an adult fairy tale, that is often read by children in wildly different — and sometimes profoundly damaging — means.

Some of that damage is obvious: the blackness child who has been verbally abused by being called a "nigger" in the schoolyard could be more injure hearing that discussion taught in the classroom, for instance. Another kind of damage less frequently discussed is how the text encourages boys and girls to believe women prevarication most beingness raped.

These damages tin be mitigated or evaded by an first-class teacher.

Students are strong enough for tough discussions; they easily can untangle the use and misuse of the word "nigger" in "Mockingbird." Merely Mayella Ewell's lies, which are the crux of the false charges brought against Tom Robinson, are far more than complicated — too complicated for the eighth grade, perhaps even with an splendid instructor.

And the book cannot continue to be taught as if every person in the classroom is white, upper heart class and needs to be prodded into existence Scout. Information technology should be taught by asking questions about why there are no black characters with bureau in the novel, by wrapping information technology in with the history of the Scottsboro boys — a grouping of black teenagers falsely defendant of raping two white women — and through raising questions nearly how "Mockingbird" (and American history) complicates the modern "believe victims" movement.

We need to exist request what we are teaching when we teach "To Kill a Mockingbird," and how useful those lessons are to 21st century students. We should be asking whether and so novel, written by a privileged daughter of the Old South should still accept up space in curriculum that could be well used to expose students to literary voices on race and injustice that take emerged in the past 50 years — voices who wouldn't accept been published at the time that Harper Lee was beginning published.

Accept, for case, "Monster," a 1999 novel by award-winning African-American novelist Walter Dean Myers that also takes place in a courtroom. Hither, however, the focus is on the young black accused and narrator, Steve Harmon; the white lawyer, on the other hand, plays a lesser, only still complex, part. Monster is a complex and powerful modern classic that does much of the aforementioned work — providing a portrait of a immature artist budding upstanding integrity while confronting racism — every bit "Mockingbird" simply does it with arguably more complication.

We are often in practice censoring books like "Monster" from the curriculum to maintain a infinite for "Mockingbird." Often, we maintain that the book'southward inclusion is in fact necessary to prevent censorship. Just what if keeping it in the curriculum maintains the condition quo of the by as much as it illuminates it? Many who defend "Mockingbird" as a choice for curriculum are imagining students emboldened by Atticus to "fight for correct" or inspired past Scout to exist better than the society into which she is born.

But imagine instead that you are an African-American eighth-grade boy in Mississippi today, and are asked to read "Mockingbird." Peradventure it reinforces your growing suspicion that you are unlikely to get a off-white trial should y'all stand up accused of something similar Tom Robinson.

Or imagine instead that you are an impoverished, white 8th-grade girl in New York today, asked read "Mockingbird." Perhaps it fuels your growing suspicion that people don't believe girls who say they have been raped — and that, should you be raped and try to tell people about it, people volition have reason to uncertainty you like the book says everyone should have doubted Mayella Ewell.

Or recollect of Calpurnia, the older black maid who cooks and serves without seeing much: she isn't developed as a character as much as written as a fix piece, suggesting the worst to immature readers nigh the role of black women and black female intelligence.

And so, of course, there is Tom Robinson, falsely accused and "crippled," in the parlance of the book, meant to indicate that he would accept been physically incapable of sexual set on. Asking a child reader to decode that artistic choice of Lee'south is to ask them to think about whether blackness men are not desirable, impotent or marred — or that rape is a criminal offense that can only exist committed by an able-bodied person.

Every student who reads Lee's volume does not identify with Atticus or with Scout, and educational activity it as though they exercise, or they must, may reinforce the very stereotypes nigh black men and impoverished women that didactics the book is supposed to combat. Some identify with Tom Robinson, or with Calpurnia, or with Mayella Ewell and, for these students, "To Kill a Mockingbird" is a far more than circuitous text which, in the hands of a less-than-effective teacher, tin can be damaging.

And so let's move beyond a argue almost censorship, about banning of books in classrooms, near the word "nigger." All of that has been hashed over more or less effectively. Characters in novels call up and human activity differently, and ofttimes in opposition to, the means in which their authors remember and act. It may be a sign that you are not a racist if you shine lite on racists by creating ane in fiction. Or information technology might not.

Allow's instead think about how, why and when nosotros invite books into our classrooms, virtually the needs of an increasingly diverse student body and well-nigh how we tin can apply hard books to both illuminate our shameful past and better shape the young minds of our futurity. Though it holds sentimental pride of place for so many as the commencement volume they read about race and injustice, "To Impale A Mockingbird" is more than a book most race and injustice, and information technology is not the only book most race and injustice. In the 21st century, it may not exist the best volume to illuminate those themes, peculiarly when it reinforces and so many stereotypes and misconceptions many 8th graders are hardly equipped to consider.

boothwheirlemse1976.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.nbcnews.com/think/opinion/why-are-we-still-teaching-kill-mockingbird-schools-ncna812281

0 Response to "Fifth Grade Essay on Why the Fine Arts Should Remain in Schools"

Post a Comment